UK Gambling Commission

November 8, 2022

- Phil Savage,

It’s a fine thing: explaining the UKGCs enthusiasm for financial penalties

As UK legislators agonize over reforms, the Gambling Commission continues to extract fines or payments in lieu of penalties at rates far beyond other regulators. Phil Savage looks at their track record and asks why and whether the industry should welcome a shakeup of the Gambling Act after all.

The long-awaited White Paper on the reform of the UK Gambling Act 2005 is yet to be published despite a consultation having started over two years ago. the most recent delay, the fifth to date, has prompted some to suggest is may never see the light of day. Reaction to the possibility that the industry will be spared the prospect of affordability checks, stake limits and bans on sports advertising and VIP schemes has, however, been surprisingly mixed. Having spent the past months fighting a rear-guard action against regulatory tightening, it seems some are now concerned that the lack of a reset will leave too much decision-making power in the hands of the UK Gambling Commission. They worry that UKGC will itself preside over a regime of ever-tightening rules and higher fines without the legitimacy of parliamentary oversight. Some have even gone so far as to accuse the regulator of having “an agenda” or of being taken hostage by the public health lobby.

Regulators are always being accused of being too close to one side or another, and most consider they have the balance about right if they are criticized equally by industry and consumer bodies. So, is the Commission really just the whipping boy for point scoring politicians, or is there more to it?

Gambling Commission CEO, Andrew Rhodes was in Australia recently talking about the number of fines handed out so far in 2022. Referencing the 16 fines issued in the year to date he said:

“At this volume, we think the message is starting to get through.”

He could also have mentioned that, at £46+ million, the total value of UK fines was, until Australia’s extraordinary £55 million penalty against Star, the highest of any jurisdiction ever, albeit that this number is skewed by the £17 million levied on Entain, itself an industry record at the time. This is not the first time the UK Regulator has led the field in enforcement fines. In fact, over the past nine years, the UK has accounted for at least 50 percent of all fines issued globally and in most years the figure is much higher.

DATA POINTS

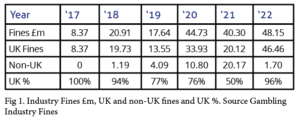

Data published by www.gamblingindustryfines.com gives ample evidence that the UK regulator has been the most ready to resort to fines of any around the world since it unveiled a new enforcement strategy in July 2017 (Figure 1).

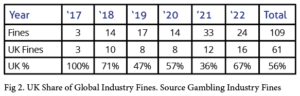

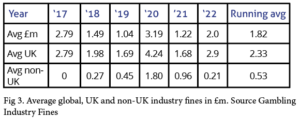

It has also issued, on average, larger fines than any other jurisdiction (Figure 2).

UK Gambling Commission fines accounted for over 75 percent of the global total in all but one year since 2017. In four of the past seven years, the UK accounted for over 90 percent of the financial total of all fines issued. The UKGC issued nine of the top-10 largest fines ever and 16 of the top-20 largest fines. The UK accounts for the vast majority (30) of all 40 six-figure fines issued globally with only Sweden (8) coming remotely close. Australia and Malta with one apiece are the only other jurisdictions to have issued £1 million+ fines.

In 2022, operators receiving fines in the UK were looking at, on average, a £2.9 million penalty as opposed to a £211,000 average penalty outside the UK (Figure 3).

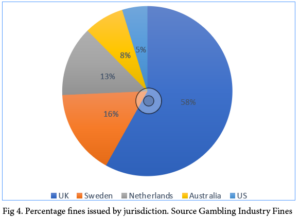

The UK also dominates in terms of the numbers of fines issued. Of the total 109 fines levied on operators since 2016, the UK accounted for 61. This is more than 3.5-times the next most active regulator, Sweden, which has issued 17 fines over its history. Netherlands at 14, Australia at 8 and the US at 5 made up the next three most active enforcers (Figure 4).

The data can be subjected to further analysis on the extent to which fines have been levied against licensed versus unlicensed operators. All of the 14 fines issued by the Netherlands’ regulator, Kansspelautoriteit, were against unlicensed operators. This is perhaps unsurprising given remote gaming was not regulated in the Netherlands until 2021, but it is notable that Holland is the only country which has tried to impose fines against those operating from outside its territory. With a channelization rate of over 95 percent, it is perhaps to be expected that the UK by contrast has only issued fines against operators holding UK licenses.

Finally, the data reveals some of the reasons behind the fines, and again there are notable differences. In 2021/22 there was a shift at the Swedish regulator to focus on the protection of problem players. Prior to this point, the majority of its enforcement actions were prompted by marketing violations and specifically the offering of bonuses. Enforcement actions by the UKGC have been for a range of offences and in many instances a coverall “Social Responsibility and AML failings” has been given as the justification for fines. What limited detail is provided relates to failure to identify source of funds in individual cases, failure in interactions with low numbers of excluded individuals and failure to identify/intervene in cases where individuals were losing large amounts of money.

MITIGATIONS?

The UK Gambling Commission has set out its principals for determining fines which, among others, includes these main points :

- The seriousness of a beach, whether a licensee ought to have known about a breach and whether a breach is a repeat offence

- Detriment to consumers and financial gain for licensee

- A premium to any amount determined by the above considerations (among others) to act as a deterrent

The lack of willingness by UK licensees to challenge the volume and levels of fines arrived under the above criteria suggests the Commission has a strong enough legal basis for levying them. But, if the UK Gambling Commission is by some distance the keenest to impose financial sanctions and increasingly willing to impose £multi-million penalties, are there mitigating circumstances which could explain its actions? Is this evidence of institutional bias or just the kind of gold-plating of regulation and enforcement for which the UK has a reputation?

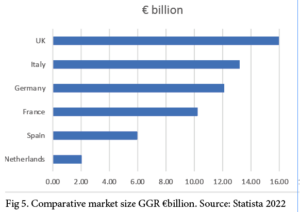

Market size: There is no real evidence that the size of the UK market alone would explain the difference in fines. The UK is broadly comparable to other markets (Figure 5) and highly channelized, so if anything, such comparisons are smaller than they might appear.

Different regulatory responsibilities: The UK regulator has a duty to ensure there are adequate controls in place at gambling companies to prevent their platforms being used for money laundering or funding of terrorism. This does not appear substantively different from other regulators, but it has emerged as the country’s most enthusiastic enforcer of anti-money laundering rules. Indeed, ten of the 16 enforcement actions taken so far in 2022 reference AML failings. The City of London’s reputation as a money laundering haven could provide an explanation except that, to date, there has been a distinct absence of prosecutions for money laundering failures in major city institutions. Neither is it right to suggest that the UK or UK operators have a worse problem with money laundering through gambling than other jurisdictions: there is no reliable data on the amounts of dirty money washed through gambling accounts. The EU’s most recent supranational report on the assessment of the risk of money laundering and terrorist financing affecting the internal market and relating to cross-border activities highlights a likely increased risk of gambling being used for money laundering and the financing of terorism but makes no attempt to quantify the situation.

The answer for so many AML-related sanctions seems to lie with the Commission’s view that targeting operator AML weaknesses is an effective way to address problem gambling.

Guy Wilkes, former head of enforcement at the UK Financial Conduct Authority told the Cambridge International Symposium on Economic Crime in September 2021 that: “the [UK Gambling] Commission uses AML requirements not just to mitigate the risk of what it calls ‘classic’ money laundering, but also as a tool against problem gambling.

“Due diligence [is required] at a fairly low level of spend, which far exceeds requirements in any other sector,” he said.

In their defense, officials have often warned that compulsive gamblers regularly turn to crime to fund their habit. Whilst they may not cash out as quickly as so-called ‘classic’ money launderers, using illicit funds to gamble still qualifies as money laundering.

In February, 2018, the Commission ordered all online gaming companies to review their compliance programs. It had found widespread failures to adopt a risk-based approach to AML and instructed operators to improve record keeping and staff training in this area. It may be that fines are more related to tardiness on the part of operators in taking a more proactive approach to prevention, rather than large numbers of specific cases of money laundering. The risk of banking services being withdrawn over AML concerns is arguably a bigger threat to the industry than fines suggesting effective leverage in this area could be achieved by other means.

Better regulation: The UK Gambling Commission could claim that its enforcement actions mean UK consumers are better protected than those in other countries, but is that the case? Data in this area is problematic with significant differences in the way countries survey and report the prevalence of problem gambling. The UK is at the lower end of the spectrum when it comes to pathological gambling, and high channelization rates would suggest that more problem play is captured within its data. Low levels of problem gambling do pre-date the Gambling Commission’s 2017 enforcement strategy suggesting no proven link between tougher enforcement and harm reduction. Logically, it would seem as easy to use low rates of problem gaming to justify a relaxation in regulation and fines as to make the argument for regulatory tightening. When enforcement actions make reference to individuals or small numbers of people who have not been adequately protected it does beg the question as to whether the level of fines is proportionate to the problem the regulation is trying to tackle.

Operator affordability: Whilst the fines appear very high, they must be looked at in the context of the size and profitability of the operators they impact. Entain’s most recent company results reported global revenues of £3.8 billion with profit before tax of £527 million. The company was fined £5.9 million in 2020 with the same offences sited by the UKGC. It may be that the regulator felt it had to triple the fine level in order to make its point. Earnings in the gaming industry have taken a hit in recent years and that is before effects of the squeeze on household earnings are considered. Going forward, it should be possible to gain the industry’s attention without larger and larger fines.

Operator indifference: A similar point to that made above, defending enforcement actions can prove more expensive than simply paying the fine and moving on. If the regulator feels fines are seen simply as a cost of doing business in the UK, then it will be tempted to make its point more strongly. Its comments that the next step would be suspension or withdrawal of Entain’s UK license should be taken seriously.

Consumer/media/political pressure: Is it possible the Commission is taking its lead from UK society in cracking down heavily on rogue operators? Every big fine is announced with some fanfare, and toughness over poor practice in the industry is frequently referenced. This is noteable where one of the UKGC’s criteria for determining fines is where a licensee adversely affects the reputation of the industry. However, it suggests the Commission feels that it is seen more positively by the public, the media and its political masters when it is taking tough action.

Whilst there are loud voices among consumer groups, sections of the media and politicians calling for greater control over the industry, it is by no means clear that a majority of opinion would support a draconian clampdown on an activity enjoyed by millions in the UK. Many have made the point that wall-to-wall advertising does the industry no favours, and it is easy to highlight the examples of individuals harmed by gambling addiction. That makes the case for a regulator to stand back from the fray and balance competing claims rather than give excess weight to the loudest voices. The Gambling Commission has a range of sanctions available to them, from the issuing warnings and imposing license conditions to suspension or revocation of licenses to the disqualification of directors. Fines may and sometimes do go with other enforcement measures but the high profile nature of financial penalties does nothing to enhance the image of the industry overall.

The public health lobby: Different from the point above, there is an argument that public health concerns should be given more weight in the debate over regulation and enforcement. Whether it concerns road deaths, victims of a pandemic or suicides among gambling addicts, there are some who argue that one death is one too many. However, those in this camp have a particularly poor record of balancing the avoidance of harm with personal freedom and responsibility, and their interventions can result in regulation which is more onerous and costly than the problem it is trying to address. A study by Public Health England (PHE), based on the opinions of 38 experts, came up with a punitive list of measures which in the view of those experts would have most impact on reducing gambling harms. These included an outright ban on in-play sports betting, website curfews and limits on the numbers playing at any given time among several other similar measures. The fact that the UKGC included contested data from PHE about the numbers of gambling-related suicides in its recent review of the UK Gambling Act 2005 (which PHE later accepted were erroneous) only adds to the suspicion that it gives undue prominence to public health arguments rather than the other way around. Indeed, some have gone further by suggesting that the UKGC appears to have been very selective in its use of PHE data and presented it in such a way as to overstate the costs of gambling-related harm way beyond what the original PHE authors were comfortable with.

REMAINING QUESTIONS

This snapshot is inevitably limited in scope, and it raises as many questions as it answers. Are UK operators guilty of more egregious violations than those in other jurisdictions? Is there evidence that high levels of fines are more effective at preventing violations? And, given the high numbers of enforcement actions and expensive fines, why is there still a clamour for new and tighter regulations? Would a different sanction regime be more effective?

Answer to these questions will have to wait for a future review. Meanwhile, it may be a case of be careful what you wish for when it comes to a White Paper.